Sometimes we ask students to do a series of tasks that are necessary for their learning, but which they would rather avoid. For example, we might assign readings for every class, or ask them to complete weekly reflections, or to post regularly on a discussion board. What do we do if our students resist doing these tasks, or if they simply don’t do them? How do we deal with their complaints: “I can’t see the point”, “it’s too hard”, “It’s too simplistic”, “I don’t like learning in that way” or “I don’t have time”.

We are asking for disciplined learning

What we are asking of our students is a disciplined approach to learning, similar to how someone learns to be a ballet dancer, a musician or a professional athlete. Disciplined learning is needed for particular kinds of learning which can only be achieved with regular training and exercise, such as being fit, being a dancer, being a musician, or being reflective. To achieve this kind of learning, students have to follow a disciplined process, supervised by a skilled coach/teacher, where they have to do things they would rather avoid.

Disciplined learning is not easy. It involves regular exercise and training for students, where we push the students beyond what they would do if they were left to their own device, like the personal trainer who shouts “just one more, you can do it!” Students might not want to do another stretch, or play another series of scales, or write another reflection, but if they don’t do these tasks regularly and frequently, week after week, they will not be able to achieve the learning objectives.

It is pointless and inappropriate for us to blame our students if they don’t do the tasks we set. There are many demands on their limited time and energy, so of course they are reluctant to squeeze in our regular learning tasks around their study, their work and their lives. Nevertheless, we know that regularly doing these tasks is necessary for their learning. There seem to be three ways we might help our students to regularly tackle these disciplined learning tasks.

1) Require students to do the tasks and support them

Make the tasks a requirement of the course. By this I mean, no exceptions to the requirements to do the task. Regular exercise and training only works if it is done regularly. If you miss the exercise you get no benefit, even if you have a good reason for missing it. So, the requirement is that students do the tasks on time, every week, no excuses. Another way of seeing this is that the tasks are the course. They are not an optional add-on to the real course which might be attending lectures, they are the course itself.

Even if you require students to do the tasks, there are various reasons why students might fail to complete the requirements, with common reasons being “I forgot” or “I ran out of time”. So, to support the students to complete the tasks you need to be like a personal trainer and monitor their performance, remind them to complete the tasks, and make them accountable for having done so. This is easiest if you specify exactly what is to be done and by when, so you, the student and the rest of the class can tell if the tasks have been completed or not. Ask students to let you know when they have completed their task, and you can also marshal the power of peer pressure and have them accountable to the rest of the class for completing their tasks. If they don’t complete the task in time, have them complete it during class time while the other students are doing something else.

However, I avoid giving grades for disciplined learning tasks. Assigning too many graded assessments is detrimental for student learning (Wass et al. 2015), and it means students are only doing the tasks for the grade. Intrinsic or personal motivation provides better encouragement. Instead of offering grades, I have something like a learning contract, where at the beginning of the course students agree to complete the tasks as a condition of doing the course.

I also avoid coercion or punishment for not doing the tasks. I think fostering personal motivation, where students choose to do the tasks, is a better way to foster learning. It is better if they voluntarily choose to complete the regular tasks, choose to be accountable for completing them, and choose to have someone act as their coach who will push them to do the tasks and help them overcome any forgetfulness or weakness of will.

2) Motivate students to do the tasks

Fostering student motivation is also essential for disciplined learning. The only feasible and ethical way to ensure students will do the tasks we assign, week after week, is if they are personally motivated to do them. So, how do you motivate students so they want to do tasks they were previously reluctant to do?

Students become motivated to complete the disciplined learning tasks when they are convinced that these tasks are important. If the students see the value of doing the tasks, see why they have been assigned these tasks, then they are more likely to voluntarily do them. So, as teachers, we need to show our students how completing the tasks is a milestone on the path to some important learning goal. We have to convince our students that the only way they can obtain something that they find valuable is via these tasks. For example, a teacher might explain how the tasks are exercises for an important learning goal, and invite past students to share how they use what they learned from these exercises. Another teacher might confront their students with problems that the students want to solve, but which they cannot solve unless they complete the tasks. A third way to show that the tasks are valuable is for you to do the tasks along with your students. This shows that you actually value the task in practice, which can be enough to motivate them to follow your lead.

However, even if our students see the value of doing the disciplined learning tasks, in a sense they still may not want to do these tasks. Even if someone knows that they can only be a great athlete by getting up before the sun to train, they still may not want to get up that early. Even if a student knows that they have to do the readings to get their dream career, they still may not want to do the readings. The problem is that we have a hierarchy of conflicting desires. On one level we can desire to avoid something, but this can be over-ridden by our higher-order desires for some bigger goal. For example, my desire to become an excellent teacher overcomes my desire to avoid writing regular reflective posts about my teaching. This hierarchy is important for understanding how we motivate students to undertake disciplined learning – we have to appeal to their higher-desires (this extends the idea of higher-order desires in Frankfurt 1971 and Cam 2016).

A third element of motivating our students is fostering confidence or self-efficacy about the tasks. Students will be more motivated if they feel they are doing well on these tasks, or at least improving (Bandura, 1982). So, teachers should use class time so students can practise doing the tasks, and they should give regular and frequent feedback to build the confidence and capacity of their students.

Build trust so students are more likely to do the tasks you set

A further way of ensuring your students tackle disciplined learning tasks, is to foster student trust. Students will be more motivated to do the tasks we assign, and more likely to complete them, if they respect their teacher, have confidence that their teacher is competent in this area of teaching, if they trust their teacher is working to support their learning, and if they trust that they will benefit from following the teacher’s instructions.

How do you build this trust and confidence in your students? One way is to show that you value your students. They are more willing to trust your methods, and go along with them, if they think you value them. Another way is to show your students your credentials as a teacher and as a subject expert. In the first class or two your students will be sizing you up, and you need to show them you care about their learning, and you know what you are doing (and even better if you do this before the first class using pre-course emails).

Doing the task with your students can also help build trust. When you do the same tasks as your students you can indicate where you struggle, and how you overcome these challenges (this is sometimes called ‘intellectual streaking’, Bearman and Molloy, 2017). This shows your students that you trust them enough to expose your mistakes and errors. It also gives your students a more accurate view of how difficult these tasks are, even for someone who is experienced. This can reassure your students that their own struggles are normal, which gives them confidence to persevere despite challenges.

Sometimes student-trust can replace student-motivation. If students really trust their teacher, they will be willing to do the tasks the teacher assigns, even if they cannot see the point of these tasks. This is the Karate Kid approach to teaching. Mr Miyagi, the karate teacher, tells his student to paint the fence all day using up-down strokes with the brush, and the next day using side-to-side strokes, and alternating right and left arms. This seems like a complete waste of time to the karate kid who rebels, but Mr Miyagi then shows him how the movements he used for painting translate to karate punches and blocks. The karate kid then realises that he can trust Mr Miyagi: If he does the weird tasks Mr Miyagi sets him, he will learn something important, even if he doesn’t understand why he is doing these tasks. He learns to trust the teaching.

Note: Some of these methods for encouraging disciplined learning will also be useful when your students resist learning the content you are teaching; They are useful methods when your students complain “Why are we learning this?” because they think the topic is boring, irrelevant or pointless.

References

Bandura, A (1982) Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2): 122–147.

Bearman, M, & Molloy, E (2017) Intellectual streaking: The value of teachers exposing minds (and hearts), Medical Teacher, 39(12), pp. 1284-1285,

Cam, P (2014) Fact, Value and Philosophy Education. Journal of Philosophy in Schools, 1(1), pp. 1-10.

Frankfurt, H (1971) Freedom of the will and the concept of a person. Journal of Philosophy, 58(1), pp. 5-20.

Wass, R, Harland, T, McLean, A, Miller, E, Sim, KN (2015) Will press lever for food: behavioural conditioning of students through frequent high-stakes assessment. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(6), pp. 1324-1326.

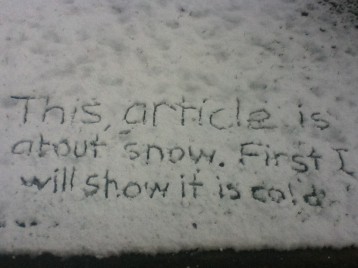

Like many people, I schedule writing time to make sure I fit it in my busy week. But sticking to your schedule is often difficult, and there are many good reasons why you might miss your writing time (like getting snowed in and unable to travel to work). Sometimes you just have to find creative ways to stick to your schedule, no matter what.

Like many people, I schedule writing time to make sure I fit it in my busy week. But sticking to your schedule is often difficult, and there are many good reasons why you might miss your writing time (like getting snowed in and unable to travel to work). Sometimes you just have to find creative ways to stick to your schedule, no matter what.