I recently organised a panel session on teaching failures. Three teaching award winners—Roslyn Kemp, Anthony Robins and Clinton Golding—shared some major failures in their teaching with a group of c.25 academics, and then we discussed what we might learn from these mistakes, and how best to relate to failures in teaching. This blog post summarises some of our ideas.

The failures we shared each involved trying something new, a major teaching innovation, that did not go to plan. Ros wanted to have all her students use I-Pads, Anthony redesigned the entire first year course for computer science (a course which fed into all the other papers offered by his department) and Clinton attempted to translate his face-to-face, discussion based teaching into distance learning and video conferencing. In each of these cases the students did not learn what we intended, hated it, or did more poorly than we expected.

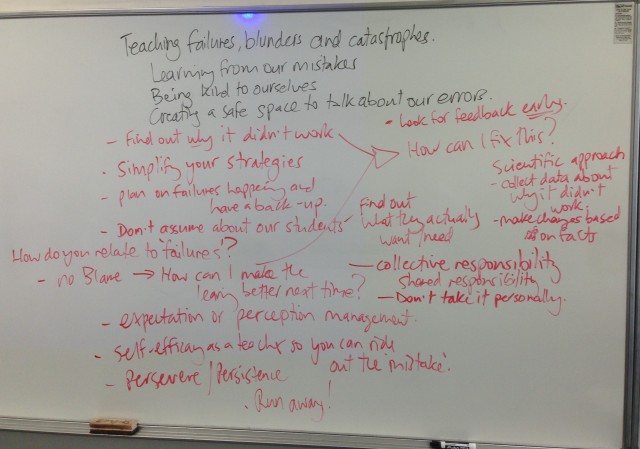

Some underlying causes of the failures:

- Overconfidence in what we could achieve. We thought, “How hard can it be?” but underestimated what we could do. For example, Clinton underestimated how hard it was to manage the video conferencing technology while also facilitating learning.

- Assumptions about what students wanted or needed, or what would appeal to them, or what they could handle. For example, Anthony tested his new course content with demonstrators, on the assumption that his first years would respond in a similar way, but he underestimated the struggles of first year students with no programming experience.

- Assumptions about what will work based on past experiences, but which did not adequately reflect our current students. We all thought, “This should work!” but we failed to think about how we were teaching new cohorts of students and we could not assume that what worked for other cohorts of students would also work with this cohort.

- Mismatch of expectations between teacher and students. We often expected one thing from the students, while the students expected something else. For example, we expected critical thinking from students, but they expected to just be told the answers.

- Overreliance on a particular piece of technology or method with no backup plan

Different kinds of failure:

- Unexpected failure. My first time teaching via video conferencing was an unexpected failure. I thought it would be no problems as I had been teaching for a very long time and had won a number of teaching awards. But I had no idea of the cognitive demand of trying to manage the content, manage the class dynamics, and manage the technology all at the same time. I ended up rapidly exhausted and went into auto-pilot teaching where I said things but I didn’t really know what I was saying, just trying to get through it. This sort of failure is inevitable in your teaching as you can’t predict everything that might happen, and you can’t tell how your teaching will land until you have taught it.

- Failure that is invisible to the students. Sometimes we see our teaching as a failure but this may not be apparent to students. For example, after my initial unexpected failure with teaching via video conferencing, I ensured I had a number of backups in my teaching such as extra readings, and times to meet with me, so that even if my new teaching methods went badly, my students would still get valuable learning. This was one of the strategies for dealing with failure: have back-up plans that mean that even if you fail it won’t be an epic failure. For example, if the technology doesn’t work, make sure you have printed handouts as back-up.

Ways to manage and mitigate our teaching mistakes

- Plan for failure, and have back up strategies available, so you make sure you provide a great learning experience for students (while realizing that unexpected mistakes can and will happen).

- Realise that the first few years of teaching something new will be sub-optimal. But you can make sure they are not sub-par. In other words have a backup so the students have a decent learning experience while you experiment with giving them a great learning experience.

- Simplify your teaching: The panel members gradually simplified their teaching so we only use essential methods with fewer and fewer ‘frills’. For example, I often only use a whiteboard without a powerpoint, and I send extra notes to students afterwards. The simple methods have fewer distractions which mean the teacher has more cognitive capacity to listen to students and help them learn. This allows for maximum flexibility and reduces the threat of failure.

- Don’t make assumptions about what will work for your students, what they will be excited by, or what they can and can’t do. Ask your students, ask colleagues who know your students (eg who know first year Physics students at Otago), and test the methods to see what does and does not work for your particular students

- If a teaching methods fails, collect evidence about why it didn’t work and use the evidence to inform what you do next. Take a scientific approach to your teaching where you collect data and make changes to your teaching based on the data. You often will have incomplete evidence and so you have to hypothesise about what will fix a problem (sometimes the evidence doesn’t make it clear what the real problem is), then try a solution, evaluate whether it worked, and try a different solution if it failed.

- Look for feedback early so you can detect an imminent failure before it is a disaster. For example, find out if students are struggling before they hand in their assignments rather than while you are marking them. Then you can reteach what they misunderstood before it is too late.

How do you relate to failures?

- No blame. It is not the students fault, and it is not your fault (unless your teaching was irresponsible or reckless where you ignored issues that you knew were likely to lead to problems). If you planned well, based on good ideas about what good teaching is, based on knowledge of your particular students, and with a plausible plan for assisting them learn, then the ‘failures’ are a necessary part of learning how to teach well.

- Be kind to yourself: Everyone makes mistakes.

- Think: There are no failures, just possibilities for getting better. Essential for my academic development

- Think: How can I fix this? How can I provide a better learning experience next time? I call this taking an improvement or enhancement approach which is very different from blaming yourself or the students which does not allow for any improvement.

- Expectation or perception management. Find out what your students expect and if it deviates from what you expect, convince them that what you expect is better. For example, convince them that even though it is harder for them to come up with the answers, they will learn more and be better prepared for careers if they think independently.

- Develop self-efficacy as a teacher so you can ride out the mistakes confident that you are a good teacher, even though it is not going well right now.

- Persevere/persistence. Change takes time. Don’t give up because of an initial failure.

- But, occasionally run away and abandon a strategy that was a hopeless failure